EDUC 766

Instructional Strategies & Assessment Methods

Course Description

Topics covered in this course:

Development of instructional goals, objectives, and assessment of outcomes.

Methods for assessing learning performance and mapping appropriate assessment methods to instructional strategies and learning objectives.

Performance-based assessment and evaluation tools to assess learner performance.

Design of formative and summative evaluation methods.

Final Project

Overview

Problem Identification

I have used instructional design principles to redesign part of a first-year writing course that I designed and developed at San Francisco State University. My redesign is focused on two “pain points.”

First “Pain Point”

One challenge I have faced is helping students embrace the writing process and recognize the value of rethinking and revising their essay drafts. Despite my efforts, it often takes significant time for students to see the importance of revision, and some never fully do.

Second “Pain Point”

Another challenge is getting students to engage productively in the peer-review process. For peer review to be effective, students must provide helpful feedback on each other’s drafts, but teaching and motivating students to do this has been difficult.

When students give one another helpful feedback on their drafts, the benefits are threefold (at least):

Students help their peers to improve an element of their draft.

Students help themselves by articulating advice that they might find helpful for thinking about their own draft (we call this “giver’s gain”).

Students foster an environment of trust, dialogue, and reflection conducive to growth and knowledge transfer.

How Instruction Will Address the Problem

To insure that instruction addresses the performance problem, I will more thoroughly integrate the concepts of writing-as-process and of helpful feedback into the course design. This will include implementing an objective method for assessing the helpfulness of feedback, which both students and instructor will use.

The concept of helpfulness of feedback will be a central or auxiliary element of many course activities. Additionally, I will regularly highlight our position in the writing process, using a map as a graphic illustration to keep students aware of their progress.

Learning Styles of Students

Students in this class are young adults, who are bursting with ideas that, for most of them, have been bottled up in high school. The key to engaging them is to give them choice in what they write about, and choice in what we focus on in the texts we read.

Students generally do not have a lot of confidence in their abilities as writers, because of the emphasis on writing in a technically “perfect” way in high school. In teaching writing as a process (which revision is an essential part of), I push back against this notion.

Personal and Social Characteristics of Students

95% of first-time freshmen at SF State go to school full time, and many work full time. For this reason, it is important that all online homework be asynchronous.

Many first-year students are experiencing an abrupt life transition (living away from home, their families, and their friends for the first time), and homesickness and mental health challenges are typical. For this reason, it is important to have some flexibility with due dates.

How the Education Will Be Delivered

To deliver the education in this in-person class, I will lean heavily on Eli Review, an online peer-review platform with a whole system of instructional media and support designed explicitly to help students come to understand writing as a multi-part process and to become better reviewers of each other’s work.

This is a tech-forward in-person class. Even when students are in class, they are online: they’ll be using Eli Review and other e-learning tools in class to collaboratively and individually create, assess, investigate. Students will submit their drafts, review their peers’ drafts, rate feedback that they received, create revision plans, and execute revisions on Eli Review—both outside of class and in class.

Eli Review is a fully developed, complex instruction tool with an easy-to-use interface. The trick is to spend sufficient time teaching students to use Eli Review. While use of Eli’s interface is pretty intuitive, best practices for peer review and revision on Eli Review are not obvious; they need to be taught and practiced a lot.

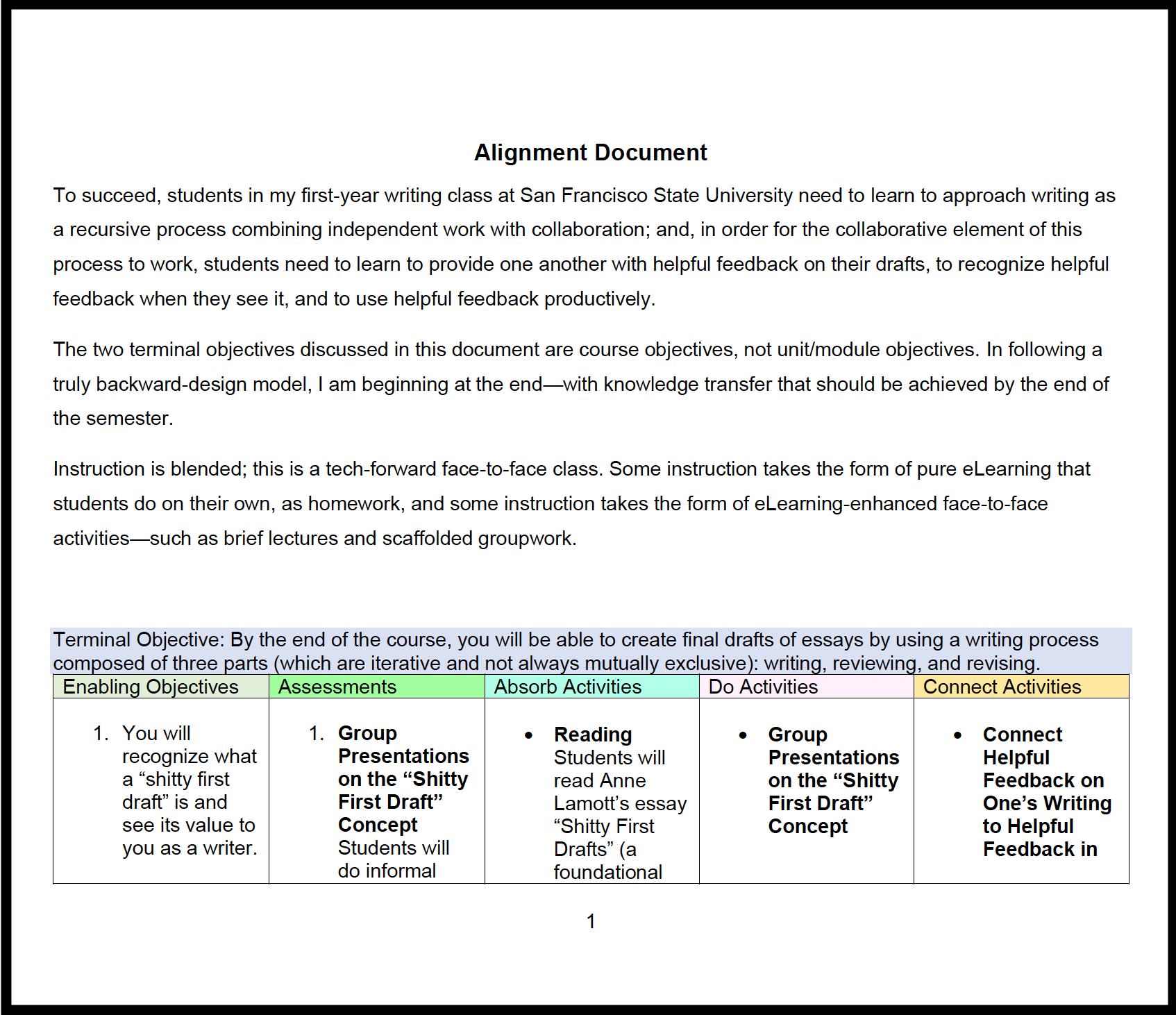

Alignment Document

Click on the the first page of the alignment document, to the right, to see the whole document on Google Drive.

I created an alignment document illustrating my systematic improvement of the first-year writing course I designed while at San Francisco State University. The alignment document makes clear that all elements of the course design—terminal objectives, enabling objectives, assessments, and activities—are coordinated and connected.

My plan for improvement of the course’s design, as illustrated on the alignment document, is based on two key learning objectives:

Students will be able to create final drafts of essays by using a writing process composed of three parts (which are iterative and not always mutually exclusive): writing, reviewing, and revising.

Students will be able to constructively collaborate with peers during the writing process, producing helpful feedback for peers and utilizing the helpful feedback they receive from peers.

The alignment document walks its reader through the backwards design that I implemented, following William Horton’s activity-design model.

Assessment

My course’s assessments are aligned with its enabling objectives. Each assessment is designed to give students the opportunity to demonstrate that they have met one, or multiple, objectives.

The assessments for my course’s first terminal objective—“Students will be able to create final drafts of essays by using a writing process composed of three parts (which are iterative and not always mutually exclusive): writing, reviewing, and revising”—are aligned with the stages of the writing process that students progress through: Writing, Reviewing, Revising.

Assessment 1

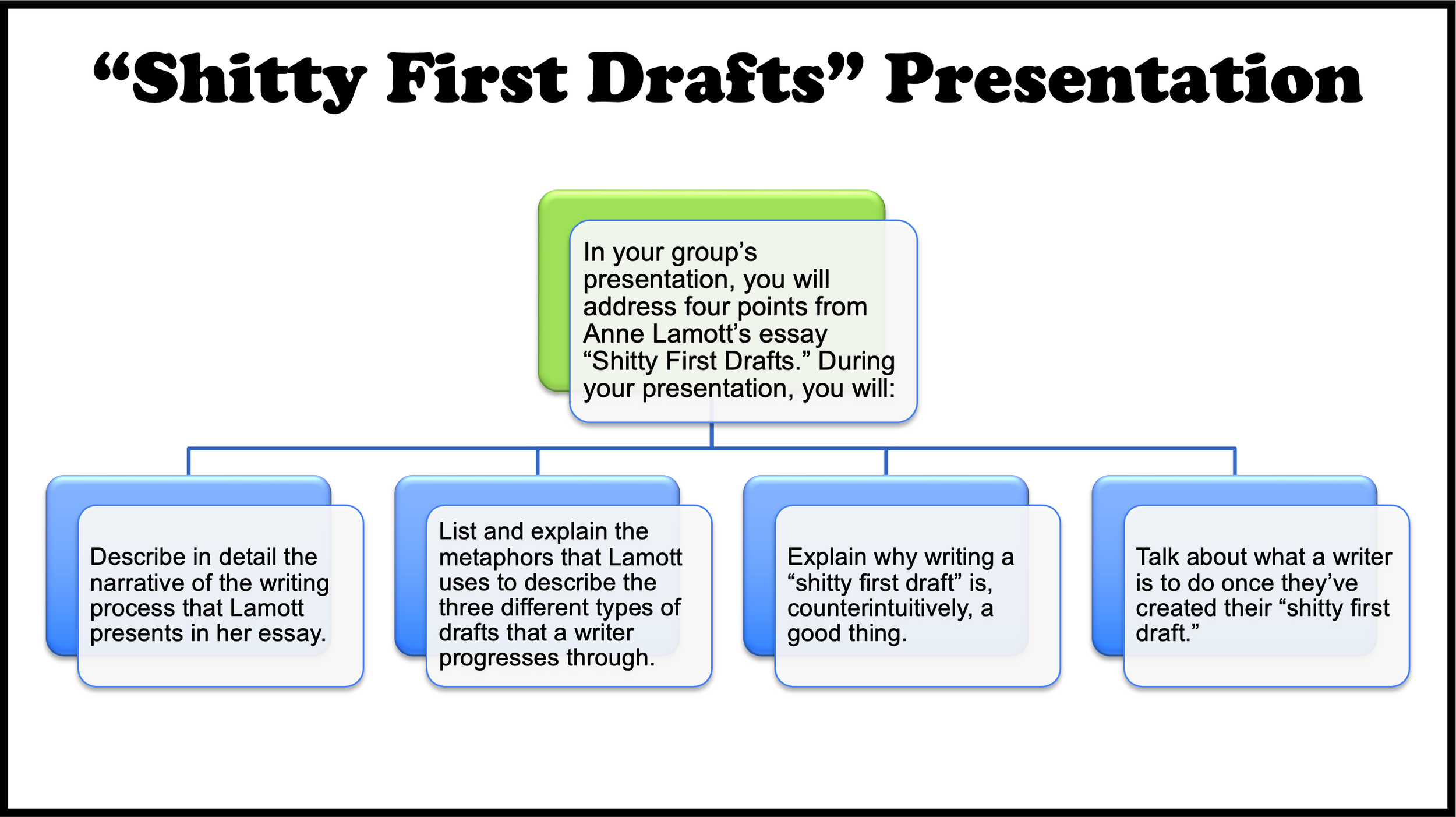

The first two assessments focus on creating a first draft—specifically what Anne Lamott calls a "shitty first draft" (an initial, highly imperfect attempt at writing that is necessary before we can revise and improve our work). To assess students’ basic understanding of the concept of the “shitty first draft,” I ask them to deliver group presentations discussing Lamott’s essay “Shitty First Drafts.” The instructions for this assessment are below:

I assess presentations using a rubric that is keyed directly to the instructions for the assignment. Assessment is formative, in that any group that does not meet the expectations of the assignment is required to re-attempt their presentation, after taking into account the instructor’s detailed feedback.

Assessment 2

For students’ second assessment, they compose a “shitty first draft.” What I am assessing here is whether students adhere to the word-count and content standards of the final draft. While it is understood that a first draft will not be one’s best work, I do want students to understand, as well, that they should try to create the best work they can when writing a first draft: This means sticking to the standards of the final draft. Students will receive feedback from the instructor on their drafts, following the peer review process—making this assessment formative.

Assessment 3

The concept of helpful feedback is central to the ethos of Eli Review, the online platform that students use in my course to review each other’s work and to make plans for revising their own work. To productively revise their essay drafts, students need to be able to give one another helpful feedback on their drafts, and they need to be able to identify and use helpful feedback when they receive it from peers. In order to give one another helpful feedback on their essay drafts, students are asked to use a model (which was created by the designers of Eli Review): Their adherence to this model is assessed. The model is described below:

Peer reviewers will:

Describe - say what you see as a reader (what the text is doing and/or communicating).

Evaluate - explain how the text meets or doesn’t meet the criteria of the assignment.

Suggest - offer concrete advice for improvement.

Students will not receive full credit for peer-review assignments unless they use the describe-evaluate-suggest model a certain percentage of the time. At the beginning of the semester, this requirement is set at 50%: Recognizing that students are learning a lot of new material at the start of the semester, and in line with cognitive load theory, some mistakes are expected. However, as the semester progresses, my expectations for their work become more rigorous. Eventually, students will be required to use the model at least 90% of the time. This assessment is formative, as students receive feedback along with their grades throughout the process.

Assessment 4

After receiving feedback on a draft, students are asked to rate the feedback on a 1-5 star scale, which was created by the designers of Eli Review. This peer assessment serves two purposes: It helps the instructor evaluate the quality of student feedback, and it aids students in learning how to give better feedback. The star ratings are linked to specific criteria, ensuring that the feedback is assessed consistently and meaningfully:

☆ One star for successful description of your work.

☆ One star for evaluation using the appropriate criteria.

☆ One star for a suggestion that offers you a next step as a writer.

☆ One star for showing respect for your draft and for you as a writer.

☆ One star for inspiring confidence that you will produce effective writing going forward.

This assessment of peer feedback is itself assessed. The instructor assesses whether students are using the ratings criteria by spot checking their ratings of feedback. If a student is “phoning in” their ratings (giving all five-star ratings, for example), I will have a chat with them in class, or I will ask them to meet with me during office hours. I will provide detailed feedback explaining why they are not receiving credit for assessing feedback, ensuring the assessment is formative.

Activity Design Model

To create the activity sequences for this class, I used the model of activity design that William Horton describes in his book E-Learning By Design, and I used the accessibility principles of the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework.

Horton breaks learning activities into three types: Absorb, Do, and Connect.

Absorb Activities

Information-focused: Designed to help learners take in and understand new information.

Passive learning: Involves reading, watching, or listening without requiring active participation.

Foundation-building: Provides essential knowledge that learners need before engaging in more interactive activities.

Goal: Ensure learners comprehend and retain key information, preparing them for deeper learning experiences.

Do Activities

Interactive: Require learners to actively participate and apply what they've learned.

Skill-building: Focus on developing and reinforcing skills through practice.

Feedback-oriented: Often include immediate feedback to guide learning and improvement.

Goal: Help learners internalize concepts by putting them into practice, enhancing understanding and retention.

Connect Activities

Application-focused: Encourage learners to apply what they've learned to real-world situations.

Bridging knowledge: Help connect new information to existing knowledge or experiences.

Critical thinking: Promote deeper understanding by challenging learners to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information.

Goal: Solidify learning by relating it to practical contexts, enhancing long-term retention and relevance.

Sample Activity Sequence

The activities below are designed to meet the enabling objective You will be able to assess peer feedback that you receive for helpfulness.

Activity 1 - Absorb Activity

Reading and Viewing: Students will read and watch the content in Eli Review’s two-part student development series: “Feedback and Improvement” and “Rethinking and Revising.”

Click on either of the fist two screenshots to go to part 1 of Eli Review’s student development series and either of the second two screenshots to go to part 2.

Activity 2 - Do Activity

Practice Assessing Feedback: In class, students will regularly practice assessing sample student feedback, holding up fingers to indicate how many stars they would give each piece of feedback and explaining their reasoning for doing so when called on.

Students hold up fingers corresponding with the number of stars they would award each piece of feedback, based on the rubric for awarding stars (spelled out above in the “Assessment” section of this portfolio). Thus, students get to practice assessing feedback in a low-stakes social-learning environment.

Activity 3 - Connect Activity

Connect Helpful Feedback on One’s Writing to Helpful Feedback in Other Situations: Students discuss whether the class’s criteria for evaluating feedback for helpfulness would be useful in other situations in their lives (in and outside of school). If they do not think the criteria would be useful as written, they revise the criteria to be relevant for other situations. Then they discuss why and how the criteria, as written or in modified form, would be relevant in other situations.

A key to knowledge transfer is recognizing the applicability of takeaways from one situation to a different situation. In this activity, students are asked to consider how the concept of helpfulness in this context is related to the concept of helpfulness in other contexts in their lives.

Activity 4 - Do Activity/Assessment

Student Assessment of Feedback: Students will give every piece of feedback that they receive on a draft a criteria-based rating of helpfulness, ranging from 1-5 stars.

Finally, after absorbing information and practicing skills, students are ready for to apply their knowledge and skills in a do activity that will be assessed. This activity/assessment is discussed in more detail above, in the “Assessment” section of this portfolio.

Accessibility Framework

The UDL framework for accessibility is centered around three foundational principles: Representation, Expression, and Engagement.

Representation:

Goal: To provide multiple ways for learners to access and understand content.

Information is presented in various formats to accommodate different learning styles and sensory abilities—e.g., text, audio, video, diagrams, and interactive media.

Expression:

Goal: To provide multiple options for learners to express what they know and how they think.

Learners demonstrate their knowledge in diverse ways—e.g., through writing, speaking, drawing, creating videos, and using assistive technologies.

Engagement:

Goal: To provide multiple ways to stimulate interest, maintain motivation, and involve learners actively in the learning process.

Offers learners various ways to engage with the material—e.g., collaborative projects, self-paced learning, gamification, and real-world applications.

The above activity sequence aligns with UDL principles as follows:

Representation: The sequence begins with an absorb activity that offers multiple forms of content—reading and video—catering to different learning preferences and sensory needs. This ensures that all students have access to the material in a way that works best for them.

Expression: The do activities provide students with various ways to demonstrate their understanding. The first do activity involves a hands-on, in-class exercise where students practice assessing feedback, allowing for verbal and non-verbal expression. The final do activity/assessment asks students to apply their skills in a more formal setting by rating feedback they receive, encouraging self-assessment and critical thinking.

Engagement: The connect activity encourages students to engage deeply with the material by relating classroom concepts to real-life situations. By discussing the relevance of helpful feedback in various contexts, students are actively involved in applying and personalizing their learning, which fosters motivation and long-term engagement with the material.

Reflection

I’ve always prided myself on being an organized and prepared instructor. However, I’ve come to realize that my course design lacked the systematic structure needed to ensure full alignment between all course elements and learning objectives.

Redesigning the first-year writing class I initially developed at San Francisco State University using instructional design principles has been a transformative experience. Previously, I relied on intuition to guide my decisions—if something felt right, I incorporated it into the course. While this approach was well-intentioned, it lacked a systematic method for ensuring that students were effectively achieving the intended learning outcomes.

Although I included learning objectives in my syllabus, as required by the university, I had no concrete way of verifying whether we were truly meeting them. My approach was to expose students to various aspects of writing and the writing process, believing that this diversity would naturally lead to improved writing skills. While this strategy had its merits, I now recognize that there is a more efficient, effective, and equitable way to teach.

By applying backward design and instructional design principles in redesigning my course—first in EDUC 765 and now in EDUC 766—I’ve created a course structure that offers greater visibility of student progress and allows for easier evaluation and continuous improvement. This new approach ensures that every element of the course is purposefully aligned with the learning objectives, leading to a more coherent and impactful learning experience for my students.